The Perilous Joys of Sheer Wilderness

Theodore Roosevelt and John Muir saved much of our natural heritage

“They paved paradise and put up a parking lot.”

Those words are in the 1970 song, “Big Yellow Taxi” by Joni Mitchell, lamenting the destruction of the natural world by developers. It’s a refrain which strikes a chord in the hearts of anybody who has witnessed the leveling of forests, the destruction of shorelines and the daming of rivers for the purpose of increasing material wealth.

The awareness that unrestrained progress would inevitably destroy our natural world was intolerable to John Muir, an American naturalist and explorer who founded the Sierra Club and persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt to establish our first national wilderness parks.

In 1903, Roosevelt visited Yosemite, guided by John Muir, who had written a letter to the president inviting him to visit the Yosemite wilderness. The two men spent three memorable nights camping, first under the outstretched arms of the Grizzly Giant in the Mariposa Grove of Giant Sequoias, then in a snowstorm atop five feet of snow near Sentinel Dome, and finally in a meadow near the base of Bridalveil Fall.

Their conversations and their shared joy experiencing the beauty and magnificence of wild Yosemite led Roosevelt to expand federal protection of Yosemite, and it inspired him to sign into existence five national parks, 18 national monuments, 55 national bird sanctuaries and wildlife refuges, and 150 national forests.

Does anyone think those places would have remained wild had Roosevelt, inspired by Muir, not acted to protect them?

“Daddy won't you take me back to Muhlenberg County

Down by the Green River where paradise lay?

Well, I'm sorry, my son, but you're too late in asking

Mister Peabody's coal train has hauled it away.” (John Prine)

Central to our human dilemma is the need to use natural resources in order to thrive while wishing for the pristine natural world to survive. We agonize over the loss of habitat for wild creatures but then hate them when they ruin our tomato plants or threaten our pets. If humans suddenly had to be hunter-gatherers again none of us would survive after we burned all the wood. We can’t all return to the primordial campfire and still run over to the neighborhood pub for a martini. Whether we like it or not, we’re all in.

How many people today can make an arrowhead or a bark-sheathed canoe or, for that matter, a fire?

So, is it that we love the idea of nature but deny its reality? Whatever else it may be, we seldom seem to realize that nature can be just as brutal and unforgiving as it is comforting. Rattlesnakes bite, lightning can kill and tornadoes are no respecters of persons. A rugged fisherman in Cornwall once told me that you pay for men’s lives whenever you buy fish. The sea suffers no one lightly.

Many years ago, before color TV and the internet and cell phones and pop-tops and squeeze bottle mayonnaise, we buddies would take to the woods and camp out in what seems as almost every summer night that it wasn’t raining. Those experiences shaped a reverence for wild things and places which remains firmly planted in memory. You build a fire. You find the North Star. You hear the owl and the whippoorwill.

Long years ago, our summer camp had the Indian name “Winnataska” and each of its wooden cabins bore the name of a native tribe, such as Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Navajo and Pueblo. We respected the original people of America without knowing much about them, even some states had Native American names: “Alabama”, “Dakota”, “Ohio” “Massachusetts” and “Mississippi”.

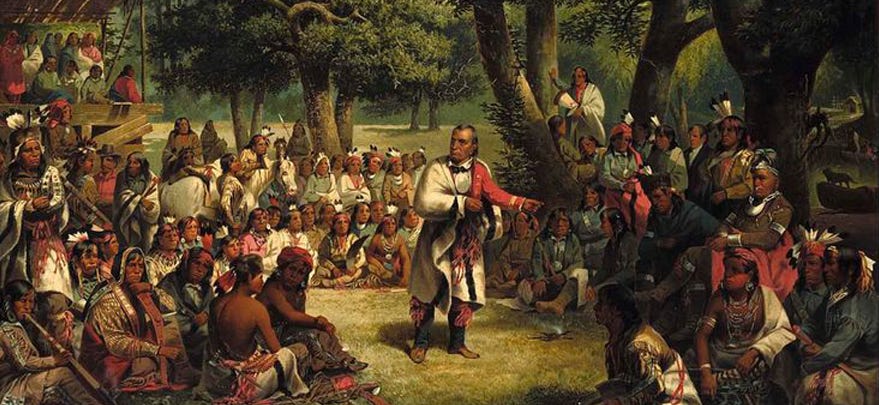

Indeed, our nation’s founding fathers patterned in part the structure of our federal government after the governing councils of native tribespeople, notably of the Algonquin, Susquehana and Iriquios tribes. Benjamin Franklin wrote about this, elaborating on the Indians’ sense of courtesy in their councils and compared them to the raucous nature of the British House of Commons.

It’s hard to imagine native American people being able to thrive in the wilderness for thousands of years with none of the tools and comforts we take for granted. But they did.

One of those things is the concept of land ownership. To the original inhabitants of America, this was beyond comprehending. How can a human being OWN a part of Mother Earth? It is so obvious that nobody owns the earth that it was never even imagined. It is, in fact, absurd. Humans are part of Nature. It is smply not possible to cut a part of Nature off and claim it as “owned” by any living thing. Earth is a gift of the spirit which made it and it is to be thankfully shared, not “possessed”.

Native Americans were so baffled by this concept that they were easily robbed by those who used it against them.

So, if we can’t go back to the cave and the campfire we can at least save some of the wild places which nurtured our distant ancestors and bring peace to our souls. Left to our own acquisitive desires, imperitives and ignorance we would, sooner or later, burn all the wood.

Thanks to the Native Americans whose wise councils tutored Benjamin Franklin and to the insights and determination of John Muir and Teddy Roosevelt, we get to keep a portion of what we otherwise would surely have destroyed.

Yes, we are grateful!/Users/kennethschultz/Pictures/Photos Library.photoslibrary/resources/derivatives/2/2299C77B-E54B-46EF-BAA6-1708ED2584F9_1_105_c.jpeg

Send it to NYTimes or National Geographic ♥️