According to both knee joints, it feels suspiciously that I may have been born around the time of the invention of the wheel. In any case, some of my childhood was spent within earshot of an ancient ice house compressor near my grandmother, Nony’s house. It’s that sort of thing which can date you as being no longer youthful. You could hear that old compressor chugging away at intervals day and night, making big, beautiful blocks of crystalline ice.

Once or twice every week, the iceman would stop his truck in front of her suburban home and haul a big, heavy block of that ice into her house and then back into the kitchen, where he would install it in a real “icebox”. I would beg, sometimes successfully, for a chunk of that ice. It was a treat on a hot summer day and, of course, was what made iced tea possible.

Iced tea, by the way, is the lifeblood of culinary culture in the South, exempted only sometimes at breakfast, making ice a daily necessity even in winter.

Nowadays we take ice so much for grated that it no longer seems special. That wasn’t the case always. In 1805, having ice in your drink was unheard of except in Northern cities, where it was harvested from fresh-water lakes and ponds in the winter months. Even then if you wanted a bourbon on the rocks, you’d have to wait ‘til December to get it and then go without it from April onward.

1805 was the year Frederick Tudor got his vision and was inspired to send ice in a ship from Boston down to the islands of the Caribbean. It was sweltering hot there most of the year so Tudor reasoned that people would love to have ice in their drinks and that once they tried it, they’d never want to give it up. He was exactly right but it took years of effort and persuasion to make it happen.

For one thing, nobody in their right mind thought you could ship frozen water into the tropics and make a profit. People in Boston scoffed at the idea and no ship’s captain could be persuaded to have a go at it. So, then, Frederick, disdaining common sense, spent nearly $5,000 of his own money to buy his own ship. It sailed out of Boston Harbor loaded with 80 tons of block ice, headed for the Island of Martinique.

Martinique! Are you nuts?

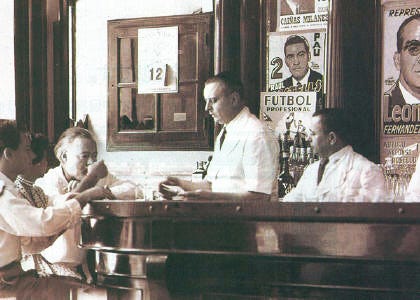

Well, the ice made it intact but nobody wanted to buy it. That didn’t stop Frederick. He finally made his first profit in 1810 and spent the next ten years creating demand for his ice in Charleston, Savannah, New Orleans and Havana. He manufactured this demand with the brilliant idea of giving away ice for one week to cafes and bartenders who would use that free ice for a week to get their customers hooked on ice-laden drinks. It worked.

“A man who has drank his drinks cold at the same expense for one week,” Tudor wrote, “can never be presented with them warm again.”

It’s an odd symbiosis that cocktails were virtually invented by the marketing of ice. If you had to have a reason for ice, well, try a whiskey on the rocks or a gin fizz and suddenly bartenders are working overtime and ice has become a necessity.

Tudor saw that his plan would make him rich and built ice houses at ports of call around the Caribbean. Mother Nature, however, was not impressed and drove temperatures so high one winter that ice could not form on the lakes. Tudor countered by hiring a large ship to sail north into the Arctic ice floes, where crewmen grappled and actually boarded an iceberg, chopped it up and squirreled it away in sawdust in the hold.

His next exploit was to outfit a ship to carry ice all the way to India, where it was greeted as a marvelous sensation. The Calcutta Courier informed its readers that Tudor deserved “to be handed down to posterity with the names of other benefactors of mankind.” The India Gazette hailed Tudor for “making this luxury accessible by its abundance and cheapness.”

Personally, I think this degree of enthusiasm for ice never made it into Europe, where ice may be perceived as “too American”. I once asked for a gin-and-tonic at a hotel bar in Ponta Delgada, in the Azores where it arrived at the table with no ice. I asked the waiter for ice. He looked dumbfounded for a few seconds then went back behind the bar, brought out a large, ornate ice bucket, reached into the freezer bin with silver tongs and ceremoniously dropped one single ice cube into the bucket, draped a white towel over his arm, brought the bucket and the tongs back out to the table then deftly lifted that lone cube and dropped it into my glass.

Mark Twain, while trekking across a glacier in France in 1886 and drinking cold water from a glacial pool, lamented the fact that the French don’t use ice. The French response was “That’s the way it’s always been.” C’est la vie, old buddy.

Today, ice can be made just about anywhere that has electricity and its use has greatly expanded from martinis and daiquiris to medicine, physical therapy and even to slow-watering your house plants. It’s pleasing to know that we were first introduced to this marvel by a tough-minded Yankee entrepreneur from Boston who never let the heat get him down. Cheers, Frederick!

There’s a great recipe for Ernest Hemingway’s very own, unique, daiquiri which I included in my first book; NAPOLEON’S CHICKEN, available by typing my name in the search bar at amazon.com.

Hemingway invented it in collaboration with bartender, Constantin Ribalaigua, at his La Floridita Bar in Havana but it appears here now and it’s yours when you become a paid subscriber.

Check it out below. You’re taste buds and I will thank you.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Eat Your History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.