*This edition is for all subscribers while next week’s will be for paid subscribers. Free and paid occur at alternate weeks. Consider becoming a paid subscriber and never missing anything, plus turning yourself into an accomplished raconteur and life of the party. ($7.00 per month, reduced to $70.00 for all 52 unique and richly loaded issues each year.)

Most kids love secret codes, which is why the old radio programs we listened to after school long ago teased us with rings that had hidden compartments or messages which we could decode only by using secret programs hidden in boxes of Wheaties or Grape Nuts.

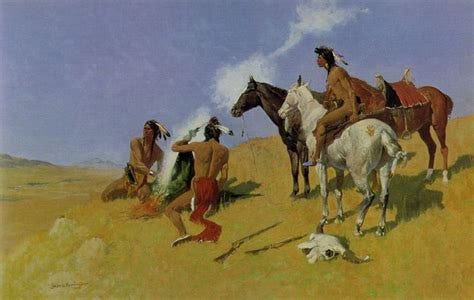

Of course you first had to send money to get the ring and you had to buy the cereal to get the program. I recall one of these offerings being a little booklet of drawings on the interpretation of Plains Indian smoke signals. Smoke signals!! Every American human younger than eight thought smoke signals were awesome. Putting the system into practice, however, was not so awesome and you could wind up just burning holes in your mother’s bath towel.

We also spent time learning to speak in “Pig Latin”; the practice of adding vowels to supplement a prefix and “ay” to the suffix, as in “oo-day oo-yay ont-way um-say ewing-say um-gay” (“do you want some chewing gum”), as if speaking English like Federico Fellini would dumbfound anybody.

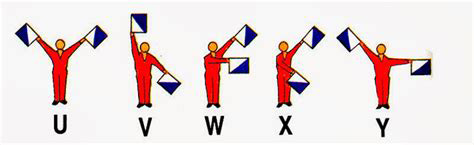

Finding out about semaphore signaling was another way to impress your fellow fourth graders, anxious to communicate across the playground without tipping off the teachers. It never caught on because learning it was too much like school itself plus it made you look weird. I failed to master it years later in boot camp but it came in handy in World War 2 when sailors could message other nearby ships in total silence, at night using lighted batons.

The most bizarre codes were called Steganography, the practice of hiding coded messages in plain sight by camouflaging them as something else. One of the most bizarre examples was written in 440 BC by the Greek historian, Herotodus. He describes how Histiaeus sent a message to Aristagoras by first shaving the head of his most trusted servant, marking the message onto his scalp and then letting the hair grow back out. The servant got his head shaved again when he got to Aristagoras.

Not all codes are for secrets

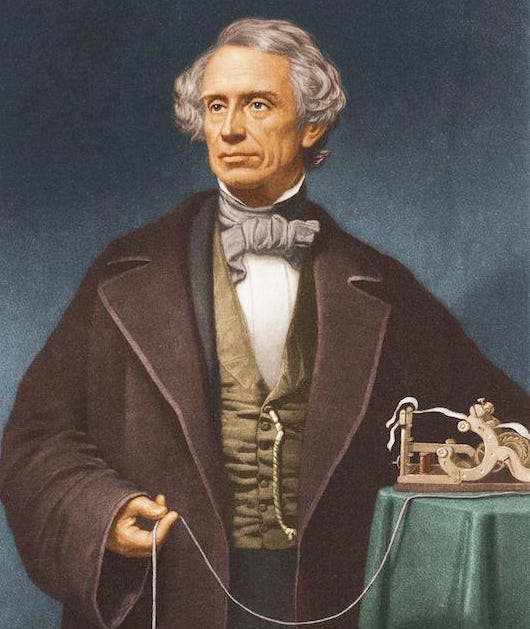

Before the internet, before smartphones, before a web of invisible data connected the world, there was a simple, elegant language of dots and dashes. The Morse Code was the first true form of digital communication, a revolutionary system that could send complex messages across continents and oceans in an instant. It is a lasting legacy that still echoes today. Our Boy Scout Handbook had the code depicted and laid out so you could master it yourself. Nobody did but we thought it was neat.

Samuel Morse was a successful portrait painter, traveling home by ship from Europe. During a conversation about electromagnets, he was struck by a revolutionary idea: if a current could be sent through a wire, why couldn’t it be used to transmit a message?

For the next decade, Morse and his associate, Alfred Vail, developed two key inventions: the single-wire telegraph and the system of dots and dashes to be used with it. In 1844, Morse sent the first public telegraph message from Washington, D.C. to Baltimore. The message, “What hath God wrought,” marked the dawn of the telecommunications age.

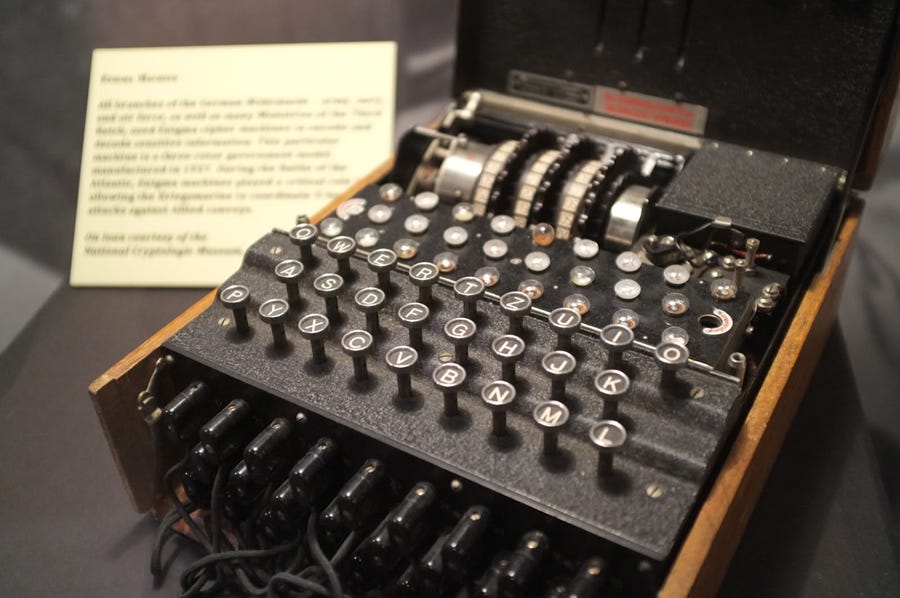

The great ENIGMA of World War 2

Breaking the code of this devilish German machine significantly shortened the war.

The Enigma code device looked like a clunky typewriter encased in a wooden box with electrical wiring plugged into it. It had rotors inside which scrambled letters into other letters. Each keystroke sent a current through a maze of circuits, lighting up a new letter on the display. For example, press “A” and the machine might spit out “X”. Press “A” again and thanks to the rotors you might get “Q”. Normal cryptanalysis simply didn’t work here.

By using Enigma, the Germans were able to coordinate the movements of submarine “wolf packs” in the Atlantic during the early years of the war, greatly harming the ability of American ships and convoys to supply men and materials to Europe and costing many hundreds of lives.

The effort to solve this problem was led by Polish and British codebreakers and was named “Ultra”. This secret program was treated as more highly classified even than the atomic bomb. If the Germans ever found out that their “unbreakable” code had been broken, the entire Allied advantage would vanish instantly.

Hard to believe, but true

With that in mind, the Allies didn’t act on every single piece of decoded intelligence lest the Germans catch on. Some convoys were thus sacrificed and attacks allowed to happen to keep “Ultra” under wraps. It was a cruel deception of our own people but the Allied commanders thought it was a vital compromise to keep the advantage. But then, they were not the ones who had to die in the icy waters of the North Atlantic.

“For me to know and you to find out”

One of the many frustrations of life in the computer age is memorizing passwords to safeguard one’s data. They are applied to bank accounts, credit cards, email programs and seemingly everything else that you have to do while not sleeping. To me, there is no better phase to summarize this than “necessary evil.” Migraines are also evil but they are not necessary.

So, “Est-bay ishes-way oo-tay oo-yay”!