The Confederacy's Loose Cannon

Fistfights, drunken brawls and duels with pistols summed up Mr. Wigfall's career

They were called “The Fire Eaters”, those hothead Southern seccessionist politicians of the period just before the Civil War. This bunch included Robert Barnwell Rhett, Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, Edward Ruffin and William Lowndes Yancy among numerous others, all of them steeped in the blood-red dye of chivalry. Their code of honor included dueling to the death over insults, improprieties and the barest hint of perceived injustice. If they had actual skin it couldn’t have been thinner.

Perhaps the hottest head of them all was a failed, alcoholic aristocrat with the unlikely name of Louis Trezevant Wigfall, a bizarre figure who tried to freelance the surrender of Fort Sumter at the war’s outset, was frequently involved in fistfights, participated in several duels with pistols and was drunk for much of his adult life, which he largely spent gambling or in taverns and whorehouses when he wasn’t inebriated in a military uniform or occupying a seat in the legislature.

This unruly individual was born into wealth but began throwing it away as soon as he discovered gambling, sex and alcohol. He managed in spite of himself to wrangle high positions in politics and the military, taking over his dead brother’s* Edgefield, SC, law practice in 1839. He squandered his inheritance and was forced to borrow money from friends to maintain his lifestyle.(* This brother was killed in a duel.)

In a five-month period, Wigfall managed to get into a fistfight, two duels, three near-duels, and was charged but not indicted for killing a man. This ended in 1840, when he was shot in the hip during a duel with ex-classmate and hated rival, Preston Brooks, whom he wounded also in the hip. For his part, Brooks, as a US senator, would later use his cane to club Massachusetts Senator Sumner Wells nearly to death on the Senate floor in May, 1862.

This initial foray into politics and the Brooks affair destroyed his law practice. He was elected delegate to the South Carolina Democratic convention in 1844, but his violent temperament and behind-the-scenes meddling had already doomed his youthful political ambitions.

Starting Over in Texas

In 1848, Wigfall moved to Texas, joining a law practice and later holding a seat in the Texas House of Representatives, emerging as a prominent member of that rousing faction of secessionists known as the “Fire-Eaters”.

He Challenges Houston …

He became a vocal adversary of Sam Houston, who had pro-Union sentiments, and actively campaigned against him during Houston's Texas gubernatorial run in 1857. In 1859, Wigfall was elected to the United States Senate as a Democrat, serving until his withdrawal on March 23, 1861, and was subsequently expelled on July 11, 1861, due to his support for the rebellion. He then was appointed to the Confederate army as a general officer.

Then He Upstages Beauregard

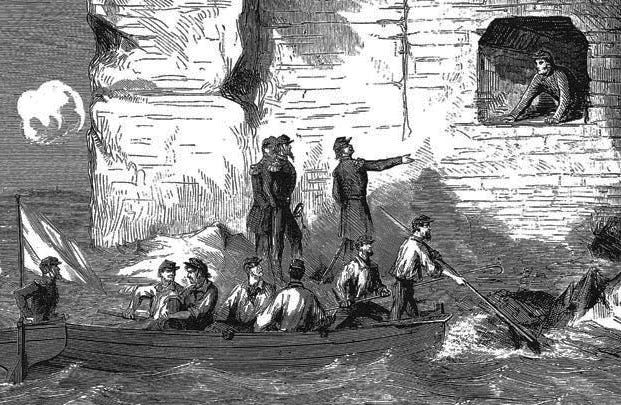

While acting as an aide to General Beauregard, the Rebel commander at Charleston, and in the middle of the bombardment of Fort Sumter, Wigfall took it upon himself to approach the fort without prior authorization. He was rowed out to the fort in a small boat which he commandeered, carrying a white handkerchief on a raised sword to demand the surrender of Major Robert Anderson, climbing into the fort through a casemate opening.

Needless to say, Beauregard, who had been painstakingly negotiating with Anderson for two long days, was blue-in-the-face furious, having been blindsided by this crazed drunk, who freelanced a surrender completely on his own. The terms offered by Wigfall had previously been rejected by Beauregard who blasted the fort to pieces and was able to negotiate the surrender on his terms.

Whiskey and Cigars refused, War Begins

The first shot came at 4:26 in the morning of April 11, after a night of protracted efforts to negotiate the surrender. Colonel James Chesnut, Captain Stephen Lee, Captain A.R. Chisolm and two others had crossed the two miles of harbor in an oar boat twice since midnight, trying to persuade Anderson to evacuate the fort. They had taken two cases of claret one case of whiskey and two boxes of cigars with them as gifts to the troops, hoping to gain favor sufficient to peacefully accept Beauregard’s demands. But to no avail. Anderson said he could not accept Beauregard’s terms and would not take the gifts.

After that, by lantern light, Anderson escorted the men to the boat ramp and shook hands with each.

“Gentlemen,” he said, “if we never meet in this world again may God grant that we may meet in the better one.”

Wigfall was never disciplined for his disruptive attempts at peacemaking.

Wigfall then took command of the Texas Brigade within the Army of Northern Virginia. During the winter of 1861–1862, he established his residence in a tavern located close to his troops in Dumfries, Virginia, where he often summoned his men to arms at midnight, driven by fears of a Federal invasion. His anxiety stemmed from drinking too much whiskey and hard cider. As a result, Wigfall's minimal effectiveness as a brigadier general diminished even further and he frequently appeared intoxicated, both on and off duty, in front of his soldiers.

After the war, Wigfall escaped to London, fearing that he would be tried and executed. While there, believe it or not, he intrigued to foment trouble between Britain and the US, finally leaving after six years of exile when he found out that he would not be arrested back home.

End Note

Just on paper alone, the South couldn’t possibly have won the Civil War. They were outdone on every social, industrial and financial measure that existed and by several orders of magnitude. And they knew it. And yet they fought it anyway and even, in some instances, came tolerably close to winning the conflict despite overwhelming odds. Cooler heads might have prevailed and the war possibly prevented if those righteously indignant “Fire Eaters” like Wigfall had not been so prominently and tragically involved in stoking the flames.

(Eat Your History is an ongoing research project to find and reveal those unexpected parts of our planet and our history which have been overlooked by the publishers of history books.

You can be a major part of Eat Your History by becoming a paid subscriber and helping me to continue providing its rich content.

It’s a real need. I hope you’ll consider it today.)

Thanks,

Bob